Animal Welfare Reform

When Promises Stall and Why Education Changes Everything

If you’ve followed animal welfare policy in the UK for any length of time, you may recognise this pattern.

A hopeful announcement.

Big language.

A sense that this time things might finally change.

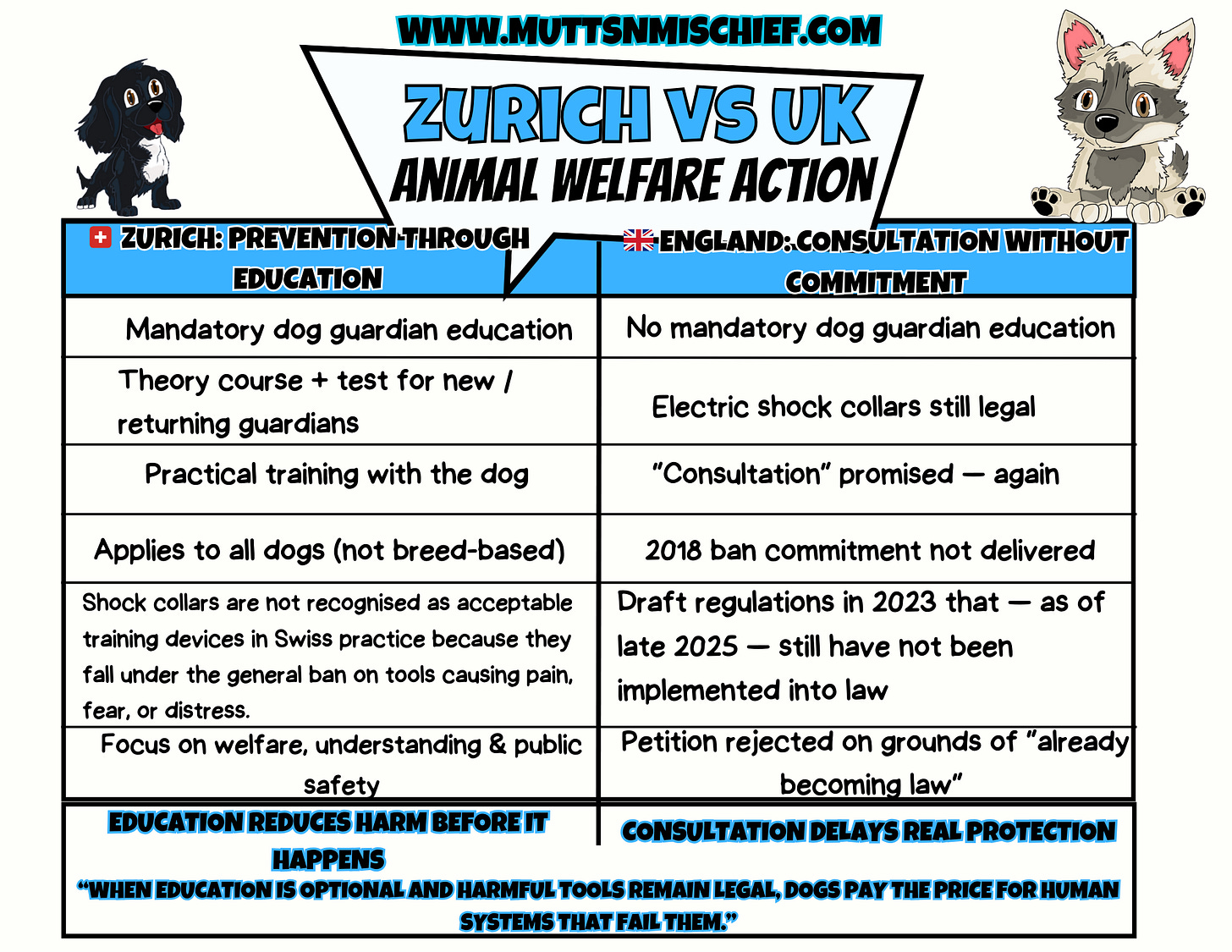

In late 2025, the UK Government released its Animal Welfare Strategy, described by DEFRA as “the biggest set of animal welfare reforms in a generation.” On the surface, it sounds ambitious — and parts of it genuinely are.

The strategy promises action on puppy farming, illegal imports, low-welfare breeding, rescue oversight, and improved standards across multiple sectors. It also promises to consult on banning electric shock collars for dogs.

And that single word — consult — is where many animal welfare professionals and advocates paused.

Because we’ve been here before.

This post isn’t about headlines or soundbites. It’s about what happens after the announcements, why trust has been eroded, and why education-led systems elsewhere in Europe are already delivering better outcomes for dogs and guardians alike.

If you’ve ever wondered why so many people remain sceptical — even when reforms sound positive — this is why.

The deeper analysis below explores the full history behind electric shock collar legislation in England, why previous commitments failed, and what the UK can learn from Switzerland and Zurich’s education-first approach.

The UK Strategy: What’s Being Promised — and What Isn’t

The Animal Welfare Strategy sets out reforms intended to be delivered by 2030. Its stated aims include tackling puppy farming, reforming low-welfare breeding, improving rescue oversight, raising standards across farming and zoos, and promoting “responsible dog ownership”.

But when we look closely, many of the most harmful practices are not being ended — they are being consulted on.

And for those of us who have tracked welfare policy over time, consultation without commitment is not neutral. It’s a delay mechanism.

Electric Shock Collars: A Timeline That Explains the Scepticism

To understand why this matters, we need to go back to 2018.

In 2018, the UK Government publicly committed to banning electric shock collars for dogs. A national consultation was launched, and the outcome was unequivocal:

the public and animal welfare professionals overwhelmingly supported a ban.

Following that consultation:

Draft legislation was developed

The Animal Welfare (Electronic Collars) (England) Regulations were prepared

Campaigners were repeatedly told the ban was “coming.” (Countryfile, 2025)

At the same time, a public petition calling, written by myself, for action was rejected by the House of Commons Petitions Committee, on the basis that a ban was already going to become law. (House of Commons Petitions Committee, 2018)

That assurance proved false.

The draft regulations were never enacted.

The ban never arrived.

And England still allows electric shock collars today. (Countryfile, 2025).

This is not a minor delay. It is a failure that fundamentally shapes how current promises are received.

England as the Outlier

Within the UK:

Wales banned electric shock collars in 2010

Scotland as a government, highly discourages the use of electric shock collars

England now stands alone — still consulting, still delaying, still allowing devices that evidence shows can cause pain, fear, distress, and behavioural fallout. (DEFRA, 2018; Countryfile, 2025)

So when the 2025 strategy promises another consultation, many advocates are asking a fair question:

Why should we trust this process without sustained pressure?

Switzerland: Where Welfare Law Draws a Clear Line

Contrast this with Switzerland.

Under Swiss animal welfare law, electric shock collars are already prohibited. Training tools that cause pain, fear, or distress are not permitted — full stop. full stop (Swiss Federal Council, 2023)

There is no ambiguity here.

No prolonged consultation cycles.

No waiting years for draft legislation to be enacted.

Switzerland has chosen a welfare-first legal framework that starts from a simple premise: causing harm in training is unacceptable.

Zurich’s Education-First Model

From June 2025, the canton of Zurich will introduce mandatory dog guardian education. (Animalcoach Zürich, 2024)

This includes:

A compulsory practical training course completed with the dog

A theory course with assessment for new or returning guardians

Requirements that apply regardless of breed or size

This is not about control. It’s about prevention. (Animalcoach Zürich, 2024)

Zurich’s framework recognises that most welfare problems do not start with “bad dogs”. They start with gaps in human education, support, and systems.

When guardians understand canine behaviour, stress, learning, and communication:

Fewer problems escalate

Fewer dogs are labelled “difficult”

Fewer people reach for aversive tools

Education reduces harm before it happens. (Business Companion, 2025)

Why This Matters Systemically

Shock collars don’t exist in a vacuum.

They thrive in systems where:

Education is optional

Support is fragmented

Welfare language exists without welfare enforcement

Consultation alone does not dismantle those systems.

Education-led legislation does.

The Question England Still Has to Answer

The UK strategy speaks about “responsible ownership”. (DEFRA, 2025)

But responsibility without education is an empty concept.

The real question is not whether reform is possible — it’s whether we are willing to move beyond promises, drafts, and consultations, and commit to enforceable welfare standards that prevent harm rather than react to it.

A Final Thought for Subscribers

The UK’s animal welfare reforms are set to unfold by 2030. That may sound distant — but history shows us that progress stalls when public attention fades.

Animal welfare does not improve by accident.

It improves because people keep asking uncomfortable questions.

If you’re reading this, you’re part of that pressure — and that matters more than you might realise.

Thank you for supporting long-form, thoughtful advocacy.

Why These Sources Matter

The sources referenced in this piece were chosen deliberately. They include primary government documents, official consultation records, and statutory animal welfare guidance, alongside reputable sector publications. Together, they provide a clear paper trail — showing not only what has been promised, but what has (and has not) been delivered. Including these references allows readers to verify claims, explore the policy context in more depth, and understand how animal welfare outcomes are shaped by legislation, consultation processes, and education frameworks. Transparency matters, particularly when discussing issues where public trust has previously been undermined.

References & Further Reading

References are provided for readers who wish to explore the evidence base and policy context in more depth.

Animalcoach Zürich (2024) Compulsory dog training courses in Zurich from June 2025. Zurich. Available at: https://www.animalcoach-zh.ch

Business Companion (2025) Animal welfare strategy for England. Available at:

https://www.businesscompanion.info

Countryfile (2025) Animal welfare reforms and the consultation on electric shock collars. Available at: https://www.countryfile.com

DEFRA (2018) Banning the use of electronic training collars for cats and dogs: consultation. London: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/animal-welfare-banning-the-use-of-electronic-training-collars-for-cats-and-dogs

DEFRA (2025) DEFRA announces biggest animal welfare reforms in a generation. London: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defra-announces-biggest-animal-welfare-reforms-in-a-generation

House of Commons Petitions Committee (2018) Petition response regarding the banning of electronic shock collars. London: UK Parliament. Available at: https://petition.parliament.uk

Scottish Government (2018) Ban on electronic training collars. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. Available at: https://www.gov.scot

Swiss Federal Council (2023) Animal Protection Ordinance (Tierschutzverordnung). Bern: Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office. Available at: https://www.blv.admin.ch

Welsh Government (2010) The Animal Welfare (Electronic Collars) (Wales) Regulations 2010. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk